Why the News Is Always Bad

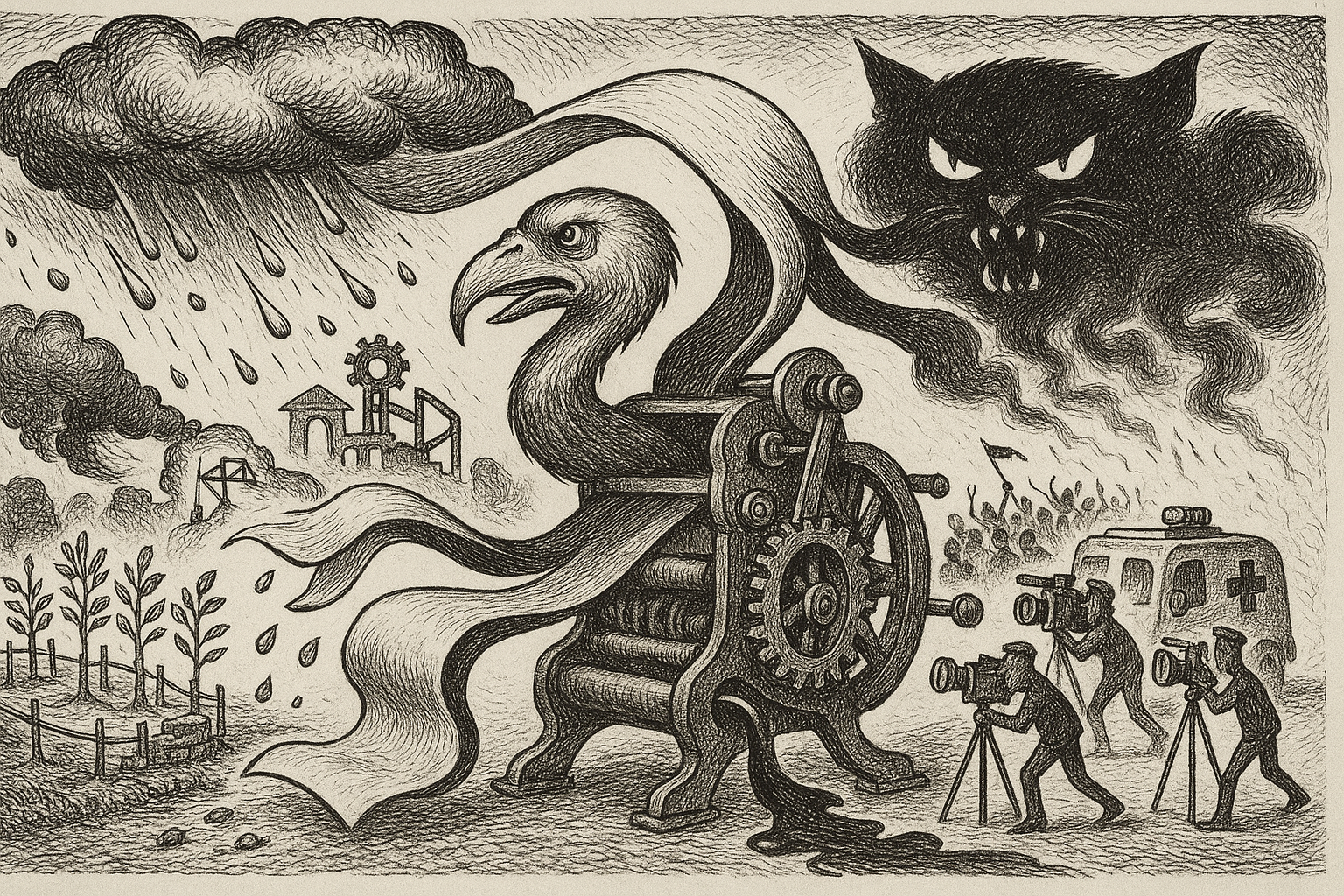

You may have noticed that the news is pretty much always bad, this has been true since before I was born, and will likely continue to be true for the foreseeable future. There are basically three forces driving this pattern. In order from the least well understood to the most: Catastrophic Asymmetry, The Toxoplasmosis of Rage, and If it Bleeds it Leeds.

Catastrophe Asymmetry

Society tends gardens of progress where good things grow like plants—slowly, visibly, predictably. Each day brings tiny changes that observers anticipate: the bridge rising span by span, the vaccine advancing through trials, the company expanding one hire at a time. These developments generate minimal surprise and thus little newsworthiness. When completion finally arrives, it feels ceremonial rather than shocking. Nobody runs through the streets shouting "Breaking news! The tomato we planted three months ago is finally red!" But catastrophes arrive like hailstorms: sudden, unexpected, demanding immediate response. It's not just that evolution gave us "tiger detectors"", gradual improvements generally have minimal information, while catastrophe usually is data dense.

This catastrophe asymmetry intensifies as change accelerates toward singularity conditions. Even miracles become catastrophes when they outpace adaptation. COVID vaccines saved millions yet generated primarily negative coverage because their public arrival compressed decades of hidden mRNA research into months of visible change, and skipped several safety steps. The dot-com revolution created unprecedented wealth, but its very speed became the story—markets couldn't price assets fast enough, creating a bubble that dominated headlines when it burst, while the subsequent decades of steady internet growth that dwarfed the bubble's wildest dreams proceeded too gradually to be newsworthy. As innovation cycles shorten below institutional response times, we're no longer cultivating gardens but caught in a permanent storm where even beneficial changes arrive too fast to process safely. The news, tasked with reporting surprises in a world built through patient cultivation, finds only disruption to report.

The Toxoplasma of Rage

The Toxoplasma of Rage, coined by Scott Alexander, explains how controversial stories dominate public discourse not because they're representative, but because controversy drives engagement in our attention-based media ecosystem. Like the biological parasite that hijacks a rat's brain to seek out cats, these "rage parasites memes" manipulate our psychology to guarantee viral transmission, making us compulsively share and argue about the most divisive cases rather than typical ones. Social media platforms and news organizations amplify this effect because conflict generates revenue, creating an information environment systematically optimized for tribal warfare rather than understanding.

There are a zillion outrages every day, you’re going to need more than that to draw people out of their shells ... a controversy.

The Toxoplasma of Rage - Slate Star Codex

The result is a discourse where the worst examples of any phenomenon become its public face, poisoning productive dialogue and driving potential allies into opposing camps. Ferguson protests dominated headlines over clearer cases of police misconduct; dubious campus sexual assault allegations go viral while representative cases remain local news; the most extreme voices crowd out moderate positions that might build bridges. This is the system working as designed, selecting for maximum engagement rather than maximum truth. Unsurprisingly, bad news is much more likely to inspire rage than good news, and so is selected upwards.

If It Bleeds, It Leads

You already know this, the phrase itself dates back to the end of the 1890s when William Randolph Hearst coined it after seeing that stories involving horrific incidents caught the public's attention. But this journalistic cynicism merely exploits a deeper neurological truth: fMRI brain scans confirm the neurological draw of bad news, showing greater and earlier blood oxygen level-dependent activation in the amygdala and periaqueductal gray when we view threats—our fight-or-flight response hijacking attention before conscious thought intervenes. A study of 105,000 headlines with over 370 million impressions found that for every positive word included in a headline, the click-through rate decreased by 1%, while each negative word increased engagement. Demand creates the supply, when one outlet refuses to serve our daily bloodletting, we simply follow the scent to whoever will.

"In keeping with Channel 40's policy of bringing you the latest in blood and guts, and in living color, you are going to see another first — attempted suicide."Christine Chubbuck, 1974, before committing suicide on live TV

This symbiosis between our primal threat-detection systems and modern media creates a self-reinforcing doom loop. Crime reporting is "cheap to cover" and "easy to cover". Just shoot the scene, shoot the blood, shoot the victims... you can do it in 20 seconds. Meanwhile, availability bias means after ingesting negative content, we overestimate its significance, we overestimate rare but sensational brain cancers while underestimating common reproductive cancers that lack shock value. The phrase "if it bleeds, it leads" describes both editorial policy and a fundamental insight: our evolutionary baggage keeps "blood and guts" as part of the news all the time.