The TRUMP Decision Pattern

April 7, 2025

President Trump behaves in ways that seem bizarre and chaotic to me. Some claim "4-d Chess", others "Raw Stupidity". I have been groping towards a framework that can predict his behavior - even when it seems contradictory on the surface. This is a second attempt, and deeply imperfect, but I feel like it's better than my previous best guesses.

This framework isn't about whether Trump's decisions are good or bad. Rather, it's a tool for understanding and predicting what he's likely to do in various situations. When testing a framework like this, the key question is: does it help explain past decisions and predict future ones better than alternative models? I'm attempting to build a useful mental model here, not make ethical judgments. Ethically I think he's a train wreck.

I've identified nine core elements of the Trump decision pattern. It mostly works across a wide range of situations, though deciding what his "current battle" is at any given time can be a bit subjective. These are specifically ordered in decending importance. Principal 1 overrides principal 3,

The Trump Decision Pattern: Nine Core Elements

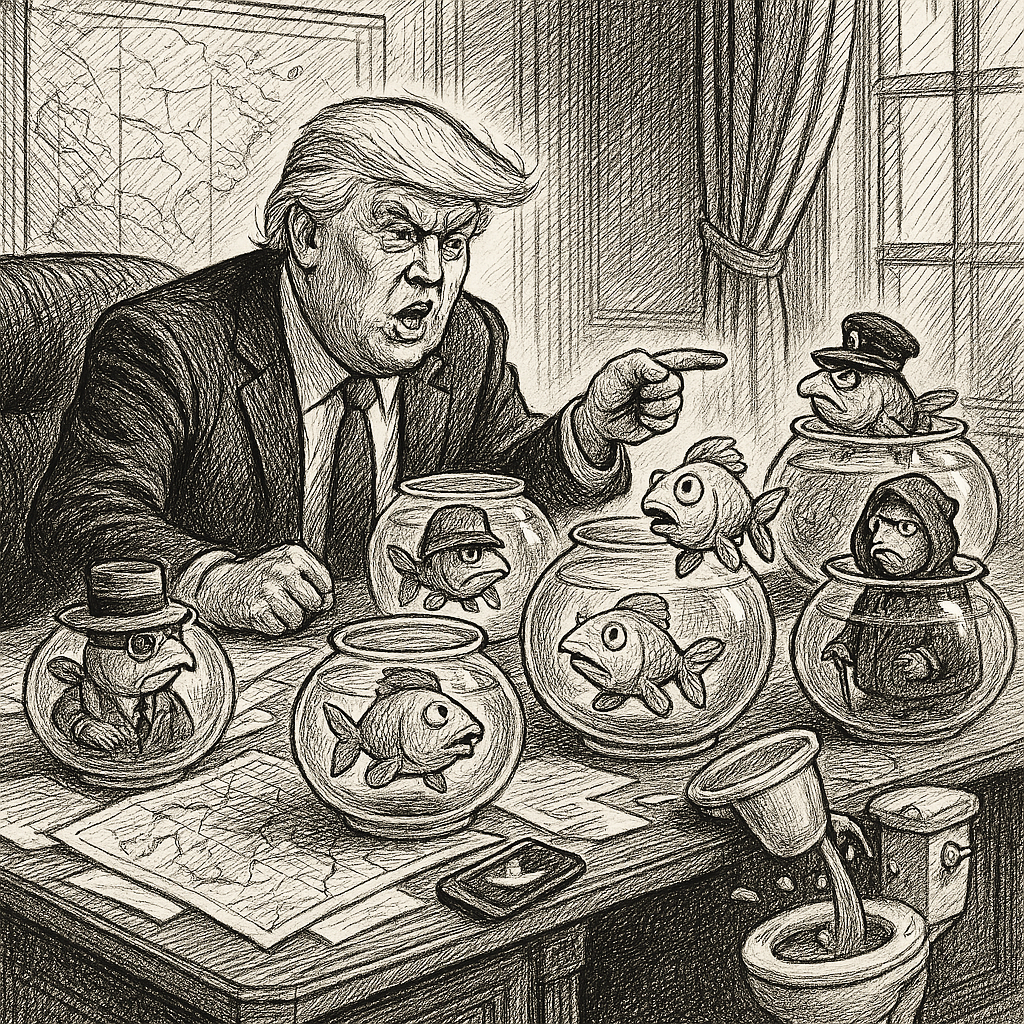

1. Win the current battle at all costs — More than willing to sacrifice larger interests (GOP, intelligence agencies, U.S. credibility) and long term success to win immediate conflicts. This is the critical thing to understand, and explains the most of Trumps crazy and erratic behavior. Trump is willing to burn down his house in order to win an argument about the color of the drapes. There simply is not a sense of value to things outside the "current battle". This makes Trump a terrifying opponent, but also means that the rest of his assets are constantly being sucked into conflict for low value trades.

2. Punitive against perceived betrayal — Savage, immediate retaliation against anyone showing disloyalty, including following due process or exercising independent judgment. Currently waging punitive war against the CIA. The conflict with intelligence agencies from Trump 1.0 "betrayals" has reached the point where Trump will probably sell out the CIA to Russia just to watch them burn. See also point 1.

3. Pro-peace as an ethical position — Wants shooting to stop, but doesn't plan for sustainable peace or think out precedent or fallout. Particularly concerned about nuclear war, though again struggles to thing more than one step forward and often makes things worse because of it.

4. Zero-sum thinking — Someone must lose for him to win; win-win only works if he's winning more.

5. Nativist core with isolationist tendencies — America-alone approach that restricts entry, and generally withdraws policy and economics from international entanglements. The obsession with tariffs is a pretty good example of this. This isn't a "good for American interests" thing... this is "america shouldn't interact with others" thing. This is ultimately pretty bad for everyone.

6. Somewhat vengeful against opponents — Unlike #2's immediate punishment of betrayal, holds calculated grudges against expected opponents, to be settled when convenient. To clarify this a little further, If he sees someone as an obvious enemy from day one (say Hillary Clinton, or Kim Jong Un) he tends to put kicking them when they are down at a pretty low priority.

7. Attack-first negotiation — Opens with actual attacks (tariffs, sanctions, etc.) before starting negotiations, then moderates terms at the table. This is one of his most erratic and horrible seeming patterns. If Trump decides he wants to say, get a discount on his sandwich, he will START by running full page ads slandering the sandwich shop, and then walk in and say, give me a 50% discount on sandwiches and I'll stop the ads.

8. Broad latitude within loyalty boundaries — Gives clear orders on priorities but grants wide freedom beyond that, as long as loyalty is maintained. This is basically a spoils system. If you are Secretary of transport he's fine if you want to paint all the busses green, or steal 20% of the budget, or re-rout a highway thru a swamp just because. The main thing is if he tells you to do something (turn off transit to the border) you need to do it immediately.

9. Unusually supportive of Russia — His approach aligns suspiciously well with Russian interests, likely due to subordinates' working relationships and latitude given. At this point everything Trump is doing seems to work out so well for russia that I'm assuming several members of his inner circle are fully manipulated. This combined with #8 and #1 leads to some really crazy stuff.

In the sections that follow, I'll test each element of this framework by examining the strongest counterexamples I could find. If this pattern is robust, it should either absorb these apparent contradictions or help us refine the model.

Testing the Model: Apparent Counterexamples

1. Win the Current Battle at All Costs

Apparent Counterexample: The 2020 Census citizenship question (2019)

At first glance, Trump's handling of the census citizenship question controversy might appear to contradict the "win at all costs" pattern. When the Supreme Court ruled against adding a citizenship question to the 2020 Census in June 2019, Trump ultimately abandoned the specific approach rather than continuing the fight indefinitely. In Department of Commerce v. New York, the Supreme Court ruled that the administration's rationale for adding the citizenship question was "contrived" and insufficient, effectively blocking its inclusion.

However, looking closer, this actually reinforces the pattern. After the ruling, Trump didn't simply accept defeat. The administration initially created confusion – Justice Department attorneys indicated they were dropping the effort while Trump tweeted the opposite. There was an unusual replacement of DOJ attorneys on the case and clear resistance to accepting the court's decision. This period of "slow-walking" compliance with the court order demonstrates that immediate acceptance of defeat was not on the table.

Most importantly, rather than truly conceding, Trump shifted tactics. He issued an executive order directing federal agencies to provide citizenship data to the Commerce Department through existing administrative records – essentially finding another path to the same goal. This wasn't "backing down" but "winning by other means."

The pattern holds: When one route to victory was blocked, Trump didn't abandon the objective but immediately sought alternative paths to achieve essentially the same outcome. The battle wasn't over the specific method (the census question); it was over obtaining citizenship data. And he continued fighting for that goal, just through different means. Clear examples of the "win at all costs" pattern include: firing James Comey to try to end the Russia investigation (2017), withholding Ukraine aid for political dirt (2019), pressuring state officials to "find" votes (2020), and using the Justice Department to target perceived enemies in his second term (2025).

2. Punitive Against Perceived Betrayal

Apparent Counterexample: Mike Pence after January 6th (2021)

Perhaps the most striking apparent exception to Trump's pattern of savage retaliation against betrayal is his treatment of Mike Pence after January 6th, 2021. Despite Pence's refusal to block certification of the 2020 election—arguably the ultimate loyalty test—Trump's response was surprisingly measured. Contrast this with Trump's treatment of other perceived betrayers: Jeff Sessions was relentlessly attacked for his recusal; John Kelly faced vicious public criticism after leaving; Anthony Scaramucci was completely excommunicated; and Liz Cheney became the target of an all-out political destruction campaign.

While Trump expressed anger toward Pence on January 6th itself, the expected scorched-earth campaign never fully materialized. Trump has occasionally criticized Pence since then, calling him "delusional" or "badly advised," but these attacks have been sporadic and mild compared to his treatment of others who crossed him.

Is this truly an exception to the pattern? Not when viewed through the lens of principle #1—win the current battle at all costs. In the days following January 6th, Trump faced an immediate existential threat: potential removal from office via the 25th Amendment, which would require Vice President Pence's initiation. On January 12, 2021, Pence formally declined to invoke the 25th Amendment despite significant pressure from Democrats and some Republicans to do so.

Trump's restrained response to Pence resembles a "prodigal son" calculation—the estranged ally who still has utility is treated differently from the irredeemable betrayer. By not burning the bridge completely, Trump prioritized the immediate battle (remaining in office until the end of his term) over the satisfaction of punishing betrayal.

This doesn't contradict the framework; it reveals its internal hierarchy. When principles #1 and #2 conflict, winning the immediate battle takes precedence over punishing betrayal. Far from undermining the model, this nuance strengthens it by showing how Trump prioritizes when facing competing imperatives.

3. Pro-Peace as an Ethical Position

Apparent Counterexample: The Soleimani strike (January 2020)

The assassination of Iranian General Qasem Soleimani via drone strike in January 2020 appears to directly contradict Trump's "pro-peace" tendencies. This high-risk operation brought the U.S. and Iran to the brink of open warfare—hardly the action of someone fundamentally opposed to military conflict. Trump's pro-peace tendencies are evident in his repeated efforts to withdraw troops from Afghanistan and Syria, hesitation to launch strikes on Iran after the downing of a U.S. drone (June 2019), diplomatic engagement with North Korea, and consistent rhetoric against "endless wars" throughout both administrations. More recently, Trump seems to want to end the Ukraine war rapidly at virtually any cost, and seems to be highly focused on ending the conflict in gaza as well.

This action may have been driven by principle #1 (win the current battle at all costs) but more obviously seems to draw a distinction between assassination and war. Trump doesn't seem to be anti-violence he seems to be anti-war. The Soleimani strike delivered a clear, decisive "win"—eliminating a high-profile enemy—regardless of potential long-term consequences. The immediate framing was that Soleimani was "terminated" and that the action was taken "to stop a war." This might have been spin, but I'm willing to take it at face value as what Trump actually saw himself as doing.

This case alsot illustrates the "no long-term planning" aspect of Trump's peace orientation. While he seems to genuinely prefer to end and avoid wars, this preference doesn't cover thinking thru how a move might start a war later. After the strike and Iran's retaliatory missile attacks on U.S. bases, Trump quickly pivoted to sanctions rather than further military escalation—consistent with his desire to avoid extended military engagement no longer a further abstract step away.

4. Zero-Sum Thinking

Apparent Counterexample: USMCA trade agreement (2018-2020)

The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which replaced NAFTA and was signed in November 2018 (taking effect in July 2020), initially appears to contradict Trump's zero-sum worldview. The agreement was often presented as beneficial to all three countries, and Trump himself occasionally used language suggesting mutual benefits rather than just American wins. Trump's zero-sum thinking is evident in his frequent framing of international relationships as competitions (calling the trade deficit with China "losing"), his emphasis on military allies "paying their fair share," his view of immigration as purely costly to America, and his consistent portrayal of diplomatic negotiations as contests to be won or lost.

However, a closer examination of how Trump discussed the USMCA reveals that his zero-sum framework remained intact. He consistently framed the deal as America reclaiming what had been "stolen" under NAFTA, which he called "the worst trade deal ever made." In his presentation, the USMCA wasn't about mutual benefit but about correcting a severely imbalanced situation.

NAFTA has been one of the worst deals in history that anybody has ever entered into

Trump claimed during USMCA negotiations.

Even more telling, upon returning to office in 2025, Trump immediately reopened USMCA negotiations in a highly confrontational manner (See: Principle #7), imposing new tariff threats against both Canada and Mexico. This strongly suggests he never viewed the original agreement as sufficiently favorable to the U.S. and saw it as merely a stepping stone to extracting further concessions.

The USMCA case actually demonstrates the nuance in Trump's zero-sum thinking: he can accept deals that provide some benefits to all parties, but only if he perceives that the U.S. (and by extension, himself) is getting the better end of the bargain. The deal wasn't presented as "everyone wins equally" but rather "America wins back what it lost, while our neighbors get acceptable terms."

5. Nativist Core with Isolationist Tendencies

Apparent Counterexample: Troop surge to Saudi Arabia (2019)

In October 2019, Trump approved sending thousands of additional U.S. troops to Saudi Arabia in response to escalating tensions with Iran following attacks on Saudi oil facilities. This deployment appears to contradict Trump's isolationist tendencies—putting "boots on the ground" in a Middle East conflict zone runs counter to his frequent rhetoric about ending foreign entanglements. Trump's isolationist and nativist inclinations are evident in his withdrawal from international agreements (Paris Climate Accord, Iran nuclear deal, TPP), attempts to reduce troop levels in Germany, Afghanistan, and Syria, opposition to NATO obligations, immigration restrictions, and his "America First" doctrine.

However, looking deeper, this deployment actually demonstrates how principle #1 (win the current battle at all costs) can temporarily override isolationist preferences when Trump perceives an immediate conflict that needs to be won. The context was a direct challenge from Iran, and failing to respond would have appeared as weakness or defeat in the short term.

Saudi Arabia, at my request, has agreed to pay us for everything we're doing. That's a first. But Saudi Arabia -- and other countries, too, now -- but Saudi Arabia has agreed to pay us for everything we're doing to help them. And we appreciate that.

Trump emphasized, converting a military deployment into a transactional financial arrangement that he "wins".

It's also worth noting that in 2019, Trump's foreign policy was still significantly influenced by traditional national security institutions (see principle #8). His ability to fully implement his isolationist preferences was constrained by established defense and diplomatic frameworks that would only be more thoroughly reshaped in his second term.

The Saudi deployment reveals an important qualification to Trump's isolationism: he wants to disentangle America from global commitments, but he wants to do so as a winner, not a loser. When faced with short-term conflicts that might make him appear weak if he withdraws, his desire to win overrides his isolationist inclinations. The isolationist principle remains intact as a general preference, but it is way down at principle #5

6. Vengeful Against Opponents

This aspect of the TRUMP decision pattern requires particular clarification, as it's easy to misinterpret. Unlike the savage, immediate retaliation against perceived betrayal (principle #2), Trump's approach to "clean opponents" – those understood to be legitimately on the opposite side of the table – is qualitatively different. A "clean opponent" means someone in a formally adversarial position, like an opposing candidate or party leader, not merely critics or commentators. Trump generally shows little concern for critics who lack power to meaningfully affect his interests.

With these opponents, Trump exhibits a pattern of limited, opportunistic vengeance – taking shots when the cost is low and the opportunity presents itself, but rarely diverting significant resources or attention from his primary goals. The vengeance is real but exists at a much lower priority tier than his immediate imperatives.

Consider his relationship with Mitt Romney, a "clean opponent" who became a vocal critic and even voted for impeachment. While Trump regularly attacks him verbally, he hasn't deployed the full weight of government power or launched a sustained campaign of destruction against him. The same pattern holds for most traditional political opponents – the revenge is petty and opportunistic rather than systematic and resource-intensive. One example of opportunistic vengeance was Trump's 2025 executive orders barring law firms that represented cases against him from obtaining government contracts – a low-cost way to punish opponents once he had the power to do so.

This pattern helps explain apparent contradictions, such as Trump working with Democratic opponents on the First Step Act (2018) or infrastructure negotiations. He easily sets aside the impulse for vengeance when there are more immediate advantages to be gained (principle #1). The vengeance isn't abandoned, but it's clearly something that opperates at a very low priority.

The key distinction: while "betrayal" by anyone who Trump> thinks should be loyal to him triggers an urgent nuclear response, opposition merely earns a place on a mental ledger of scores to be settled when convenient, often with some sort of implicit perception of respect. This vengeance is a background process that activates opportunistically rather than a driving imperative that overrides other goals.

7. Attack-First Negotiation

Apparent Counterexample: North Korea diplomacy (2018-2019)

Some have pointed to Trump's diplomacy with North Korea as a counterexample to his typical attack-first negotiation style, citing the eventual personal meetings and seemingly warm correspondence with Kim Jong Un. After initial hostilities, Trump appeared to adopt a surprisingly conciliatory approach, even speaking fondly of the North Korean dictator—behavior that seems at odds with his usual aggressive opening posture. Clear examples of Trump's attack-first negotiation style include: imposing tariffs on China before trade talks (2018), threatening to withdraw from NATO before demanding increased defense spending (2018), applying "maximum pressure" sanctions on Iran before suggesting talks (2019), and imposing steel tariffs on Canada and Mexico before USMCA negotiations.

However, this narrative overlooks the crucial beginning of the engagement, which perfectly matches the attack-first pattern. Trump initiated the relationship with North Korea in 2017 with unprecedented threats, famously warning of

fire and fury like the world has never seen

and mockingly calling Kim "Little Rocket Man." Trump escalated tensions further in January 2018 with his tweet about the nuclear button:

I too have a Nuclear Button, but it is a much bigger & more powerful one than his, and my Button works!

This extreme opening—threatening literal nuclear war—was the quintessential shock-and-awe tactic. Only after establishing this maximalist position did Trump pivot to direct engagement. The subsequent conciliatory behavior wasn't the negotiation strategy; it was the walk-back phase that typically follows Trump's opening salvos.

What makes the North Korea case appear unusual is simply the dramatic swing from extreme threats to personal diplomacy. But this wide pendulum swing is actually characteristic of Trump's approach—beginning with maximalist demands or threats, then moderating to a more workable position once the other party has been destabilized.

The pattern holds true: the attack-first negotiation style refers specifically to how Trump opens negotiations, not how he conducts them throughout. The fire-and-fury threats were precisely the shock-and-awe opening that's characteristic of his approach, making North Korea a confirmation rather than a contradiction of the pattern.

8. Broad Latitude Within Loyalty Boundaries

The final two principles of the TRUMP decision pattern require clarification rather than counterexamples.

The "broad latitude within loyalty boundaries" principle might appear contradicted by instances where Trump suddenly overrode or reversed initiatives started by officials within his administration—such as when he tweeted to cancel sanctions that Treasury Secretary Mnuchin had just announced on North Korea, or when he publicly undercut FDA initiatives that didn't conflict with his stated priorities.

However, these interventions don't actually contradict the pattern. Trump grants latitude but his priorities remain paramount. He is happy to let his underlings play with his toys however they want, but still views them as his toys.

This creates an environment where subordinates have de facto freedom—not because Trump respects their opinion, but because his attention is limited and selective. They can pursue initiatives freely until and unless Trump happens to need their department for his "current battle" Stephen Miller provides a clear example of effective navigation of this dynamic—he advanced dramatic immigration policies with minimal interference by maintaining absolute loyalty while quietly expanding his operational domain.

9. Unusually Aligned with Russia

Apparent Counterexample: Lethal aid to Ukraine (2017-2019)

The Trump administration's decision to provide Javelin anti-tank missiles to Ukraine in late 2017 stands out as a significant counterexample to the pattern of policies that align with Russian interests. The pattern of alignment with Russian interests is evident in Trump's hostility to NATO, his withdrawal from the INF Treaty without replacement controls, his abrupt pullout from Syria that benefited Russian positioning, his persistent defense of Putin personally, his undermining of election interference findings, his CIA purges, and his second-term reduction of support for Ukraine.

What makes this example particularly striking is that the Obama administration had previously refused to provide this type of lethal aid, making Trump's policy actually tougher on Russia in this specific area. The missiles were genuinely delivered and put to use—there wasn't a backdoor undermining of the policy.

However, examining the context reveals important factors that help reconcile this apparent contradiction. This decision came very early in Trump's administration, when he was still working with his initial foreign policy team, including Defense Secretary James Mattis and Secretary of State Rex Tillerson. Both were establishment figures with traditional views on Russia who still maintained significant influence at this stage. There was also strong bipartisan congressional pressure for arming Ukraine, including from key Republicans whose support Trump needed on his broader legislative agenda.

This was also before the deeper rifts developed between Trump and the intelligence community. In late 2017, he hadn't yet become disillusioned with intelligence agencies and was more receptive to their assessments and recommendations regarding Russia and Ukraine.

The Ukraine aid case reveals how principle #1 (win the current battle at all costs) and principle #8 (broad latitude to underlings) override the Russia alignment when other priorities take precedence.

So What will Trump Do Next?

At the top of the hierarchy sits principle #1—winning the current battle at all costs. This imperative consistently overrides all others when immediate victory is at stake. The critical trick here is figuring out what the "current battle" is at any given time. To the extent that you can tell what Trump is focused on, you have a pretty good clue. In lulls between active battles it's harder to figure out what's going to come up next.

Next comes the punitive response to perceived betrayal (principle #2), which is only deferred when it would directly interfere with winning a more important immediate battle. The savage retaliation against disloyalty is not abandoned, merely postponed until it can be exercised without compromising higher-priority goals. Any time you see something that Trump might perceive as "disobedience", it's worth expecting some over-the-top attacks soon.

When he launches strange and unprovoked huge attacks against others, it's probably a sign that he's about to open negotiations with them.